Headline 1

here’s the body of the first article

Headline 1

here’s the body of the first article

The Second Vatican Council, in its “Declaration on Non-Christian Religions” (Nostra Aetate), taught that “the Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in [other] religions,” and encouraged Catholics to “recognize, preserve and promote the spiritual and moral values as well as the social and cultural values to be found among them.” Following this direction, the All India Seminar in 1969, which was attended by the hierarchy and representatives of the whole Catholic Church in India, spoke of the “wealth of truth, goodness and beauty in India’s religious tradition” as “God’s gift to our nation from ancient times.” The seminar showed the need of a liturgy “closely related to the Indian cultural tradition,” and theology “lived and pondered in the vital context of the Indian spiritual tradition.” In particular, the need was expressed to establish authentic forms of monastic life in keeping with the best traditions of the Church and spiritual heritage of India.

The Second Vatican Council, in its “Declaration on Non-Christian Religions” (Nostra Aetate), taught that “the Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in [other] religions,” and encouraged Catholics to “recognize, preserve and promote the spiritual and moral values as well as the social and cultural values to be found among them.” Following this direction, the All India Seminar in 1969, which was attended by the hierarchy and representatives of the whole Catholic Church in India, spoke of the “wealth of truth, goodness and beauty in India’s religious tradition” as “God’s gift to our nation from ancient times.” The seminar showed the need of a liturgy “closely related to the Indian cultural tradition,” and theology “lived and pondered in the vital context of the Indian spiritual tradition.” In particular, the need was expressed to establish authentic forms of monastic life in keeping with the best traditions of the Church and spiritual heritage of India.

The Second Vatican Council, in its “Declaration on Non-Christian Religions” (Nostra Aetate), taught that “the Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in [other] religions,” and encouraged Catholics to “recognize, preserve and promote the spiritual and moral values as well as the social and cultural values to be found among them.” Following this direction, the All India Seminar in 1969, which was attended by the hierarchy and representatives of the whole Catholic Church in India, spoke of the “wealth of truth, goodness and beauty in India’s religious tradition” as “God’s gift to our nation from ancient times.” The seminar showed the need of a liturgy “closely related to the Indian cultural tradition,” and theology “lived and pondered in the vital context of the Indian spiritual tradition.” In particular, the need was expressed to establish authentic forms of monastic life in keeping with the best traditions of the Church and spiritual heritage of India.

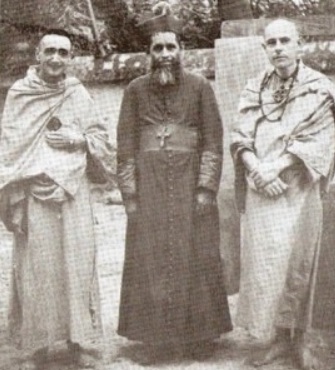

Anticipating the Second Vatican Council and the All India Seminar, “three wise men from the West”––the title given by Br. John Martin referred to Jules Monchanin, Henri le Saux, and Bede Griffiths––founded the pioneer Christian ashram in India, Saccidananda Ashram, which is usually known by its other name, the name of the piece of land on which it is built––Shantivanam.

Shantivanam, Saccidananda Ashram, is a Camaldolese Benedictine monastic community in South India. “Shantivanam” means literally the “forest (vanam) of peace (shanti),” and is located near the village of Tannirpalli in the Tiruchirapalli District of Tamil Nadu, on the banks of the River Kavery. It was first founded in 1948 by the French priest Jules Monchanin, who would later adopt the name Parma Arupi Anananda, “the supreme joy of the Spirit,” and a French Benedictine monk Henri le Saux, who was later to adopt the name Abhishiktananda––“bliss of Christ,” by which he would come to be widely known.

These monks sought to identify themselves with the Hindu “search for God,” the quest for the Absolute, which has inspired monastic life in India from the earliest times. They also intended to relate this quest to their own experience of God in Christ in the mystery of the Holy Trinity. Together, the two wrote a book about their experiment, entitled An Indian Benedictine Ashram, which was later re-published under the title A Benedictine Ashram. The goal of le Saux and Monchanin was to integrate Benedictine monasticism with the classic Indian model of an ashram. They adopted the way of life of an Indian sannyasi (renunciate), wearing kavi (saffron colored) robes and adopting a strictly vegetarian diet.

“Saccidananda” is a classic Hindu description/name for the Divine. It is literally translated as “being (sat), knowledge or consciousness (chit), and bliss (ananda). It was adopted by Christians such as Keshub Chandra Sen and Brahmadapad Upadaya early as the late 19th century as the name for and an intimation of the Christian Holy Trinity, the 1st Person, normally called the Father, as Sat-Being; the 2nd Person, the Word, which Christians was made flesh in Jesus, as chit–knowledge or consciousness; and finally ananda, the bliss of the 3rd Person, the Spirit. The name of the monastery was a reflection of Jules Monchanin’s attempt to blend Christian and Hindu mysticism together; but it was also a reflection of Monchanin’s firm commitment to Christianity. Monchanin, who was more of an intellectual than le Saux, was hesitant to identify the Hindu Vedanta concept of Advaita–non-duality with the Holy Trinity, stating that “Christian mysticism is Trinitarian or it is nothing.” He did, however, believe that with a lot of work it was possible to reconcile the two mystical traditions, and this was the principle upon which Saccidananda Ashram was founded. This integration of the Vedanta with Christianity is a point upon which these two original founders of Saccidananda Ashram differed. Abhishiktananda was more radical in his thinking: while Monchanin held to the idea of Christianizing other religions, soon on Abhishiktananda (who often referred to Monchanin as his “Christian Guru,”) came to believe that non-Christian religions could transform Christianity itself.

A Belgian Trappist monk named Francis Mahieu joined them in 1953, who then went on to found Kurisumala Ashram with Bede Griffiths, an English Benedictine, in 1958. Fr. Bede himself stayed at Saccidananda Ashram in 1957 and 1958. Sadly, Fr. Monchanin died in 1957 while back in France for a medical procedure. As the years went by Abhishiktananda preferred to spend more and more time in the north of India where he had a hermitage in the Himalayas rather than at Shantivanam. So it happened that Fr. Bede Griffiths and a group of monks from Kurisumala in Kerala came and took over stewardship of Shantivanam in 1968. Under his charismatic leadership, Shantivanam became an internationally known center of dialogue and renewal.

Fr. Bede had been officially exclaustrated from Priknash Abbey in England for his first decades in India, and eventually joined the Camaldolese Benedictine Congregation due to his friendship with Don Bernardino Cozzarini, who spent time at the ashram with Fr. Bede and introduced him to the Camaldolese prior general, Don Benedetto Calati, who was very sympathetic to Fr. Bede’s pioneering work. On the feast of St. Romuald, June 19, 1985, two Indian brothers made their solemn monastic profession and one his temporary vows as members of the Camaldolese Congregation of the Order of Saint Benedict, and the ashram became officially a member of that congregation which it remains to this day.

Life at the ashram

Among the gifts given by God to India, the greatest is thought to be that of interiority––the awareness of the presence of God dwelling in the heart of every human person and every creature. This interiority is fostered by prayer and meditation, the contemplative science of Yoga, and way of sannyasa. “These values,” it was said, “belong to Christ and are a positive help to an authentic Christian life.” Consequently it was said, “Ashrams where authentic incarnational Christian spirituality is lived, should be established, which should be open to non-Christians so that they may experience genuine Christian fellowship.” The aim of Shantivanam has always been to bring the riches of Indian spirituality into Christian life, to share in that profound experience of God that originated in the Vedas, was developed in the Upanishads and Bhagavad Gita, and has come down to us today through a continual succession of sages and holy men and women. From this experience of God lived in the context of an authentic Christian life, the community of Shantivanam hopes to continue to assist in the growth of a genuine Indian Christian liturgy and theology.

The life at the ashram is based on the Rule of St. Benedict, the patriarch of Western Monasticism and on the teaching of the monastic Fathers of the Church, but the monks also study Hindu spirituality and philosophy (mainly the Vedanta) and make use of Indian methods of prayer and meditation, and yoga. In this way, they hope to assist in the meeting of these two great traditions of spiritual life by bringing them together in our own experience of prayer and contemplation.

In externals, the community follows many of the customs of a Hindu ashram, wearing the saffron (kavi) colored robe of the sannyasi, sitting on the floor and eating with one’s hands. In this way, they seek to preserve the character of poverty and simplicity that has always been the mark of the sannyasi in India. One distinctive feature of the life is that each monk lives in a small thatched hut, which gives him a greater opportunity for individual prayer and meditation, as well as creating an atmosphere of solitude and silence. There are two hours specially set apart for meditation, the hours of sunrise and sunset, which are traditional times for prayer and meditation in India.

The ashram seeks to be a place of meeting for Hindus and Christians, people of all religions or none, who are genuinely seeking God. For this purpose there is a guesthouse, where both men and women can be accommodated for retreat, recollection, and religious dialogue and discussion. There is a good library, which is intended to serve as a study center. It contains not only books on the Bible and Christian philosophy and theology but also a comprehensive selection of books on Hinduism, Buddhism, other religions and a general selection on Comparative Religion. Many visitors come from different parts of India and from all over the world who are seeking God by way of different religious traditions. The ashram responds by providing an atmosphere of calm and quiet.

For those who seek to become permanent members of the community, there are three stages of commitment to the life of the ashram. The first is that of sadhaka, that is the seeker or aspirant. The second is that of brahmachari, one who has committed himself to search for God, who need not remain permanently attached to the ashram. The third is that of sannyasi one who has made a total and final dedication, when the kavi robes are given and one is committed for life to the search for God in renunciation of the world, family ties and one’s self, so as to be able to give oneself entirely to God. This however need not involve a permanent stay in the ashram; in accordance with Indian traditions the sannyasi is also free to wander or go wherever the Spirit may lead.

The ashram is attentive not only to spiritual seekers but is also conscious of the poor and the needy neighbors in the surrounding villages. Though the ashram’s primary call is to discover “the kingdom of God within,” it is also deeply proactive to the cry of the poor in their milieu through the words of Jesus “whatever you do to the least of my brothers and sisters that you do unto me.” The ashram runs a Home for the Aged and Destitute; it is involved in educating the poorest children of the community; it also repairs and builds houses for the homeless. Thus the ashram gives free boarding and lodging and medical care to 20 aged and the destitute, and over 400 children receive books, school uniforms and clothes every year. In addition we care for children below three years of age by providing fresh cow’s milk.

The ashram supports itself partly by cultivating 8 acres of land in its possession; by a dairy farm and from the contributions received from the visitors and well-wishers. As the monks say about themselves, “In our serious efforts to support ourselves and the poor around, we constantly remind ourselves, the visitors and the poor we serve that the ashram is primarily a place of prayer, where they can experience the presence of God in their lives and know that they were created not merely for this world but for eternal life and where they find God.”

inculturation

In the ashram’s prayer, use is made of various symbols drawn from Hindu tradition, in order to adapt our Christian prayer and worship to Indian sacred traditions and customs according to the mind of the Church today. The church itself is built in the style of a South Indian temple. At the entrance is a gopuram or gateway on which is shown an image of the Holy Trinity in the form of a trimurti–a three headed figure

The community meets for prayer three times a day: in the morning after meditation, when the prayer is followed by the celebration of the Holy Eucharist; then again at midday and in the evening. At each of the prayers, together with psalms and readings from the Bible, there are also readings from the Vedas, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita as well as from Tamil classics and other Scriptures. They make use of Sanskrit and Tamil songs (bhajans) accompanied by various percussion instruments. They also make use of the arati, waving of lights and incense before the Blessed Sacrament and other sacred elements, and several other Indian customs, which are now generally accepted in the Church in India. In this way they hope to assist in the growth of a truly inculturated Indian liturgy.

In the Morning Prayer, the forehead or the hands are marked with sandal paste as a way of consecrating the body and its parts to God. Sandalwood is considered the most precious of all woods, and it is therefore seen as a symbol of divinity. As it is also has a sweet fragrance, a symbol of divine grace; it is also a symbol of the unconditional love of God since it gives its fragrance even to the axe that cuts it. As one’s body is marked, we are reminded that we, too, need to give that unconditional love of God to all in our daily living. At the Midday prayer, a purple powder known as kumkum is used. This is placed on the space between the eyebrows and is a symbol of the “third eye” the eye of wisdom in the Indian tradition. As the brothers explain it, “Our two eyes are the eyes of duality, which see the outer world and the outer self, whereas the third eye is the inner eye which sees the inner light according to the Gospel, if thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light. This single eye is the third eye, which was often marked on Greek icons of Christ, and is thus a universal symbol. In India the red colour is considered to be feminine, the mark of mother goddess. We consider that it symbolizes the feminine wisdom, which we attribute it Our Lady of Wisdom.” Midday prayer is a wisdom prayer consisting of the Wisdom Psalm 118 and a reading from one of the Wisdom books of the Jewish scriptures. At the Evening Prayer ashes known as vibhuti are used. The symbolism here is not merely like that of Ash Wednesday––“Dust thou art, unto dust thou shalt return”––but has a deeper meaning as well. Ash is the final product of the matter from which the impurities have been burnt away. Placing the ashes on the forehead signifies that our sins and impurities have been burnt away and we have become the purified self.

At each of the prayers, an arati is offered before the Blessed Sacrament. Arati consists in waving of burning flame and/or incense in a circular motion before any sacred object or person as a sign of honor worship. In the central shrine in the temples of India the inner sanctuary is always kept dark to signify that God dwells in the guha, the “cave of the heart.” And the burning flame waved before the shrine reveals the hidden God. So the burning flame is waved before the Blessed Sacrament to manifest the hidden Christ therein. After venerating the Blessed Sacrament, the flame is then brought around and each member of the assembly places their hands over the flame and takes the light of Christ to their eyes by.

Every Hindu puja consists in the offering of the elements to God, as a sign of the offering of all creation to God. Just so at the Eucharist at Shantivanam, in a rite that is deeply appreciated by many visitors, at the Preparation of the Gifts during the Eucharist an offering is made of the four elements, water, earth, air and fire, as a sign that the whole creation is being offered to God through Christ as a cosmic sacrifice. The presider first sprinkles water round the altar to sanctify it, and then sprinkles water on the people to purify them. Then finally he takes a sip of water to purify his own inner self, before offering the “fruits of the earth and work of human hands”––the bread and the wine. Next eight flowers are placed on the tali–the sacred plate on which the gifts are offered. These eight flowers, which are offered while Sanskrit chants are being sung, represent the eight directions of space and signify that the Mass is offered in the “Center” of the universe thus relating it to the whole creation. This is followed by an arati with incense representing the air and then with camphor representing fire. Thus the Mass is seen to be a cosmic sacrifice in which the whole creation together with all humanity is offered through Christ to the Father.

In their daily prayer, the community makes constant use of the sacred syllable OM. This word has no specific meaning. It seems to have been originally a form of affirmation rather like the Hebrew “Amen.” It is normally conceived as the primordial sound, the original Word, from which the whole creation came. In this it is a kin to the Word of St. John’s Gospel, of which it is said that it was in the beginning with God and without it nothing was made. In the Upanishads, it came to be identified with the highest Brahman, that is with the Supreme reality. Thus it is said:

I will tell you the Word that all the Vedas glorify,

all self-sacrifice expresses,

all sacred studies and holy life seek.

That is OM.

That Word is the everlasting Brahman;

that Word is the highest end.

When that sacred Word is known,

all longings are fulfilled.

It is the supreme means of salvation.

It is the help supreme.

When that great Word is known

one is great in the heaven of Brahman.

For us Christians, of course, that Word is Christ.

References

Collins, Paul M. (2007). Christian inculturation in India. Liturgy, worship, and society. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-6076-7.

Cornille, Catherine (1992). The Guru in Indian Catholicism: Ambiguity Or Opportunity of Inculturation. Louvain Theological and Pastoral Monographs 6. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-0566-9.

Coward, Harold G.; Goa, David J. (2004). Mantra: hearing the divine in India and America (2nd ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12961-9.

Kim, Sebastian C. H. (2008). Christian theology in Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68183-4.

Robinson, Bob (2004). Christians meeting Hindus: an analysis and theological critique of the Hindu-Christian encounter in India. Regnum studies in mission. OCMS. ISBN 978-1-870345-39-2.

Teasdale, Wayne (2001). The Mystic Heart: Discovering a Universal Spirituality in the World’s Religions (5th ed.). New World Library. ISBN 978-1-57731-140-9.

Trapnell, Judson B. (2001). Bede Griffiths: a life in dialogue. SUNY series in religious studies. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4871-7.

Further reading

Monchanin, Jules; le Saux, Henri (1951). An Indian Benedictine Ashram. Tiruchirapalli: Saccidananda Ashram.

Vattakuzhy, Emmanuel (1981). Indian Christian sannyāsa and Swami Abhishiktananda (doctoral thesis). Theological Publications in India.

Elavathingal, Sebastian (2000). “Saccidananda Ashram — Narsinghpur: a New Paradigm for Inter-Religious Dialogue”. TM 3: 67.

Elnes, Eric (2004). “June 25–27, Days 53–55: Shantivanam Ashram”. Eric’s Sabbatical Journal. Scottsdale Congregational United Church of Christ.

Summer 2016

Summer 2016

THE BEDE GRIFFITHS SANGHA

www.bedegriffithssangha.org.ul

Back in 1993, soon after the death of Father Bede, a small group met at a retreat house in Wales called The Skreen. Led by Ria Weyens, then a member of the Christian Meditation Community in London, the ten of us created a weekend retreat based on the rhythm of the day at Shantivanam. We met three times a day for prayer, including readings from different traditions and singing bhajans and chants from Shantivanam.

This little group called itself the Shantivanam Sangham, but later, as numbers grew, we changed the name to the Bede Griffiths Sangha. This was to make it more accessible to the large numbers of people who have been inspired by Father Bede; his vision for the renewal of contemplative life and the renewal of Christianity in the light of Vedic philosophy and spirituality.

Numbers grew and we have over 600 people on our mailing list – mostly in the UK but also from all over the world. Over the last 25 years or so we have met regularly for retreats and conferences. For many years the old Prinknash Abbey was where we met for our Advent retreat. Some of our retreats are quite active – more like contemplative seminars, others are silent. We have published a newsletter several times a year for almost a quarter of a century., most of which are available on our website.

LATEST NEWS

LIVING from the GROUND of BEING:

Continuing the dialogue East and West

Conference followed by an optional silent retreat

JUNE 16 th – 18 / 19 th 2017

At Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre

Birmingham – UK

Fr Brian Pierce & Br Martin Sahajananda

in contemplative conversation

The speakers will lead us, and invite us into ‘contemplative conversation’

together. This sort of dialogue was described by Fr Laurence Freeman of WCCM in his 2016 Lent reflections:

We are all part of a conversation. The word ‘conversation’ usually evokes

the sense of speaking together but this is a late meaning – from the

16th century I think. Its original meaning is suggested by St Benedict’s

vow of ‘conversatio morum’, change in values and our way of life. (…)

Conversation is primarily about ‘turning towards’ something together,

training our attention on a common point and ‘living together’ in that way of looking and seeing. To look at is not always to see. But you have to look first before you can truly see what is.

THE PROGRAMME:

The Conference:

Each day will follow the pattern as at Shantivanam Ashram, that is, three periods of silent meditation together with morning, midday and evening prayers. We end the day with Nama Japa (chanting the name of Jesus) and then keep silence until after breakfast. Integrated into this rhythm will be a programme of talks, contemplative conversation, and periods of meeting in small groups. There will be time to walk in the 10 acre grounds with a lake, a labyrinth and conservation area. The conference finishes after lunch on Sunday 18 th .

Optional Silent Retreat:

We are also offering a 24 hour silent retreat at the end of the conference, at the same venue and at extra cost. The speakers will join in this, and the format will arise from the conference.

It will not be possible to come to the retreat only. The retreat finishes after lunch on Monday 19 th .

THE VENUE:

The Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre, Selly Oak, Birmingham B29 6LJ is based in the Grade II listed building which used to be the home of George Cadbury the Quaker chocolate manufacturer, and benefactor. 49 of the 60 bedrooms are en suite and there is a mixture of single, double and twin bedrooms. There are a conference room and 3 smaller rooms available for our conference, and full board using produce from the garden and ethically produced sustainable food products. For further information see www.woodbrooke.org.uk

WANT TO COME?

For details of cost options and for booking go to:

www.bedegriffithssangha.org.uk

How I Pray

Bede Griffiths

If anyone asks me how I pray, my simple answer is that I pray the Jesus prayer. Anyone familiar with the story of a Russian pilgrim will know what I mean. It consists simply in repeating the words: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” I have used this prayer now for over 40 years and it has become so familiar that it simply repeats itself. Whenever I am not otherwise occupied or thinking of something else it is almost mechanical, just quietly repeating itself, and other times it gathers strength and can become extremely powerful.

I give it my own interpretation. When I say, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God”, I think of Jesus as the Word of God, embracing heaven and earth and revealing himself in different ways and under different forms to all humanity. I consider that this Word “enlightens everyone coming into the world”, and thought they may not recognise it, it is present to every human being in the depths of their soul. Beyond word and thought, beyond all signs and symbols, this Word is being secretly spoken in every heart in every place and at every time. People may be utterly ignorant of it or may choose to ignore it, but whenever or wherever anyone responds to truth or love or kindness, to the demand for justice, concern for others, care of those in need, they are responding to the voice of the Word. So also when anyone seeks truth or beauty in science, philosophy, poetry or art, they are responding to the inspiration of the Word.

I believe that the Word took flesh in Jesus of Nazareth and in him we can find a personal form of the Word to whom we can pray and to whom we can relate in terms of love and intimacy, but I think that he makes himself known to others under different names and forms. What counts is not so much the name and the form as the response in the heart to the hidden mystery, which is present to each one of us in one way or another and awaits our response in faith and hope and love.

When I say, “have mercy on me a sinner”, I unite myself with all human beings from the beginning of the world, who have experienced separation from God, or from the eternal truth. I realise that, as human beings, we are all separated from God, from the source of our being. We are wandering in a world of shadows, mistaking the outward appearance of people and things for reality. But at all times something is pressing us to reach out beyond the shadows, to face the reality, the truth, the inner meaning of our lives, and so to find God, or whatever name we give to the mystery which enfolds us.

So I say the Jesus prayer, asking to be set free from the illusions of the world, from the innumerable vanities and deceits with which I am surrounded. And I find in the name of Jesus the name which opens my heart and mind to reality. I believe that each one of us as an inner light, an inner guide, which will lead us through the shadows and illusions by which we are surrounded, and open our minds to the truth. It may come through poetry or art, or philosophy or science, or more commonly through the encounter with people and events day by day. Personally I find that meditation, morning and evening, every day, is the best and most direct method of getting in touch with reality. In meditation I try to let go of everything of the outer world of the senses, of the inner world of thoughts, and listen to the inner voice, the voice of the Word, which comes in the silence, in the stillness when all the activity of mind and body ceases. Then in the silence I become aware of the presence of God, and I try to keep that awareness during the day. In bus or train or travelling by air, in work or study or talking and relating to others, I try to be aware of this presence in everyone and in everything. And the Jesus prayer is what keeps me aware of that presence.

So prayer for me is the practice of the presence of God in all situations, in the midst of noise and distraction of all sorts, of pain and suffering and death, as in times of peace and quiet, of joy and friendship, or prayer and silence, the presence is always there. For me the Jesus prayer is just a way of keeping in the presence of God.

I find it convenient to keep in mind the four stages of prayer in the medieval tradition –lectio, meditatio, oratio, contemplatio. Lectio is reading. Most people need to prepare themselves for prayer by reading of some sort. Reading the Bible is the traditional way, but this reading is not just reading for information. It is an attentive reading, savouring the words as in reading poetry. For this reason I prefer the authorised or revised versions of the Bible, which preserve the rich, poetic tradition of the English language.

Lectio is followed by meditatio. This means reflecting on one’s reading, drawing out the deeper sense and preserving in the “heart”. It is said that Mary “pondered all these things in her heart”. This is meditation in the traditional sense, bringing out the moral and symbolic meaning of the text and applying it to one’s own life. The symbolic meaning goes beyond the literal and shows all its implications for one’s own life and for the life of the Church and the world. It is a great loss when the literal meaning, of which today, of course we have a far greater knowledge, leaves no place for the deeper, richer symbolic meaning which points to the ultimate truth to which the Scripture bears witness.

Meditation is naturally followed by prayer – oration. Our understanding of the deeper meaning of the text depends on our spiritual insight and this comes from prayer. Prayer is opening the heart and mind to God, that is, it is going beyond all the limited processes of the rational mind and opening the mind to the transcendent reality to which all words and thoughts are pointing. This demands devotion – that is, self-surrender. As long as we remain on the level of the rational mind, we are governed by our ego, our independent rational self. We can make use of all kinds of assistance, of commentaries and spiritual guides, but as long as the individual self remains in command we are imprisoned in the rational mind with its concepts and judgements. Only when we surrender the ego, the separate self, and turn to God, the supreme Spirit, can we receive the light which we need to understand the deeper meaning of the scriptures. This is passing from ration to intellectus, from discursive thought to intuitive insight.

So we pass to contemplatio. Contemplation is the goal of all Christian life. It is knowledge by love. St Paul often prays for his disciples that they may have knowledge (gnosis) and understanding (epignosis) in the mystery of Christ. The mystery of Christ is the ultimate truth, the reality towards which all human life aspires. And this mystery is known by love. Love is going out of oneself, surrendering the self, letting the reality, the truth take over. It is not limited to any earthly object or person. It reaches out to the infinite and the eternal. This is contemplation. It is not something which we achieve for ourselves. It is something that comes when we let go. We have to abandon everything – all words, thoughts, hopes, fears, all attachments to ourselves or to any earthly thing, and let the divine mystery take possession of our lives. It feels like death and is a sort of dying. It is encountered with the darkness, the abyss, the void. It is facing nothingness – or as Augustine Bakes, the English Benedictine mystic said, it is the “union of the nothing with the Nothing”.

This is the negative aspect of contemplation. The positive aspect is, of course, the opposite. It is total fulfilment, total wisdom, total bliss, the answer to all problems, the peace which surpasses understanding, the joy which is the fullness of love. St Paul summed it up in the letter to the Ephesians – or whoever wrote that letter which is the supreme example of Christian gnosis: “I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that according to the riches of his glory, he may strengthen you with his spirit in the inner man: that Christ may dwell in your hearts by faith, that being rooted and grounded in love, you may have the power to comprehend with all the saints what is the length and breadth and height and depth, and may know the love of Christ which surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.”

Bede Griffiths

First published in The Tablet April 1992

Probably the English speaking world’s foremost teacher of Celtic Spirituality, John Philip Newell and his wife Ali and four children have devoted themselves to a new vision of reality. Newell’s shared vision resembles Father Bede’s vision and life-long devotion to returning our sacred planet to health and wholeness by assisting in the process of balance – between male and female, creation and creature, God and humanity, and the world’s religions.

John Philip Newell celebrates the sacredness of the universe under the belief that everything that exists is made of God. Newell sees that an essential part of the pathway towards healing in our world is to become more deeply conscious of our brokenness, individually and collectively. Newell teaches that transformation will come in our lives and world to the extent that we choose to bear the cost of transformation. Newell’s practice of spirituality is his belief that meditative discipline and prayer serve the way of transformation.

Born on May 4, 1953 in Ontario, Canada to a Christian pastor who was director of World Vision Canada, Newell was reared in the Newell family ministry. Yet, during his young adulthood John Philip made pilgrimage to India and spent time at Shantivanam. “As a young man I spent time with Bede Griffiths, an English Benedictine monk who lived most of his life in India. In the East, in the wisdom and meditative practices of Hinduism, he found what he called ‘the other half of his soul.’ Like the wise men, he needed to go beyond the boundaries of his homeland, beyond the boundaries of his inherited tradition, in order to see more deeply, more truly. This also was my experience in India at Bede Griffith’s ashram. On the second afternoon of my visit I awoke from a siesta in which the briefest of dreams had come to me. In the dream a beautiful young Indian woman, dressed in a sari, sat on the edge of my bed and leaning over me looked into my face and said, ‘My mother tells me that I have always loved you.’ I awoke amidst floods of tears. Sometimes when truth deeply pierces us we weep. It is as if something has been set free to flow again in our depths.

Some would say that I should have known that I was loved. My religious tradition had told me that. And I had been blessed by a loving family and reared with a strong sense of self-worth. So, some would say that I should have known this. But I didn’t. There was a place deep within me that did not know, and I believe there is such a haunted place in most of us. For me it took a visit to the East. It took a messenger from the unconscious clothed in the garb of India for me to remember, or maybe for me to know truly for the first time in my whole life, what my religious tradition had been trying to teach me, that God is Love. Do you know that you are loved? Do you know it in the heart of your being? This is the truth of epiphany, that you are loved, that you are part of this beautiful Light of God, that you too are called to shine for the healing of the world.”

Fastforward to 2013 and Newell has launched the Praying for Peace Initiative in New Mexico to nurture greater relationship between Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and in 2011 co-founded Salva Terra: A Vision Towards Earth’s Healing www.salvaterravision.org. The Bede Griffiths Trust extends our deepest gratitude to John Philip for sharing his vision that came in a dreamtime awakening so many years and miles away from Scotland, Canada, and USA where Newell leads most of his retreats, workshops and pilgrimages today.

Fr Bede and Swami Abhishiktananda in the 21st Century

One of the things that became clear in Shantivanam during the course of 2010—a year bookended by conferences for the centenary of Swami Abhishiktananda (9-15 Jan 2010 and 14-17 Dec 2010)—was the value and increasing relevance today of Fr. Bede’s and Sw. Abhishiktananda’s work. Rather than trailing off and fading away with the passage of the decades since their deaths, what we seemed to be seeing this year and in recent years is a growing attraction to the teaching these founders imparted through their combined literary corpus and by the example of their respective monastic careers. One indication of this increased interest is simply the swelling guest ministry at the Ashram over the last couple of years. The 2010-11 season, for example, was booked throughout (and bookings for 2011-12 are filling up)—a happy problem that hasn’t been there since Bede’s time. Many who are coming are pilgrimage groups from the West. Some are Church groups, such as Patrick Woodhouse’s group from Well’s Cathedral, an annual pilgrimage made by a vital group composed largely of Anglican clergy from Wells Cathedral and surrounding dioceses. Other groups include students such as the Chigwell School which comes each February or the young Danish student group last January, among them a number of aspiring comparative religion students. Russell and Asha’s group brings forty or more each season. Doctoral students of theology and Catholic and Anglican religious are finding their way to Shantivanam in increasing numbers by way of Bede’s and Abhishiktananda’s writings. 2010-11 also saw two separate French film crews (headed by Vincent Lauth), one doing a documentary on Abhishiktananda’s life (not to be confused with the 2006-7 German film crew led by Gunter Franke) and a second, filming a documentary on Christian Ashrams for French national television (France 2). An ecumenical interfaith dialogue center of prayer in South Africa which has taken Shantivanam’s namesake (calling itself Sat Chit Anand), regularly includes in its newsletters reflections inspired by Bede’s books and Br Martin’s talks.

But 2010-11 brought not only an increase in numbers at the Ashram, but seemed to engender a qualitative shift, a synergy of presence and an intensity of purpose among those gathered that was not there before. So why all this sudden interest in Shantivanam, Fr. Bede, Swami Abhishiktananda and the East-West encounter?

Perhaps it is several things. To be sure the conferences last year, drawing sincere dedicated scholars, writers, priests, pundits, monks and nuns from all over the world, came as a fresh breeze inspiring we India-based participants and nudging us back to the work that had brought us down this path in the first place. It was an eye-opener and pointed to a vital dimension of Shantivanam’s growing ministry—one that is yet to be fully exploited: Shantivanam’s role as a convener, hub and headquarters for ongoing research in the East/West dialogue and the Christian Ashram experiment. But the trend of the 2010 conference year was already in place before the year began. Indeed Br. Martin’s ministry in Europe has been growing year by year in recent years and many who have the chance to see him in Europe are drawn to visit the Ashram. Camaldolese oblates from Italy and the US are learning of Bede and Shantivanam through their contacts with the Camaldolese. Cyprian’s world-wide music and teaching ministry has raised awareness about East-West dialogue and Fr Bede in remote regions of the world, and his Santa Cruz-based Bede Sangha (which recently did a benefit concert in Santa Cruz for Bless School [situated near Shantivanam]) made a pilgrimage to Shantivanam a few years ago, inspiring numerous follow-up visits by its members. The Bede Sangha in the UK and their outreach work in Tannirpalli has raised interest at home and brought their own groups to Shantivanam.

The gradual dissemination of information about the mission of Shantivanam spreads with new publications, elevating Shantivanam’s profile in other countries, e.g., Shirley Du Boulay’s biographies of Bede and Abhishiktananda, Medio Media’s reprinting Bede’s books with worldwide distribution, and ongoing translation of Abhishiktananda’s writings into various languages. But if Fr Bede’s and Swami Abhishiktananda’s ideas are propagating and reaching larger audiences, still the question remains, why only now?

Arguably the social changes we are seeing globally are playing a part. The increasing interculturation in Western societies, for example, has lent a sense of immediacy to the language of accommodation and interfaith bridge-building across religious and ethno-cultural lines. Since Bede and Abhishiktananda’s time, history has made ecumenism not just a good idea but essential, even inevitable. If no man is an island, then in this age of globalization, no religion is either, and the need for mutual understanding—if not mutual interpenetration bridging denominational divides—is proving indispensable. To be sure, as Fr Bede would have been quick to point out, this work can only be effective in the context of an authentic appreciation of one’s own tradition and knowing how to place oneself and one’s tradition within the overall scheme of a radically and rapidly changing globalised social and theological landscape. But as the ground shifts beneath our feet and the very fabric of individual and collective spiritual psychologies and modes of articulation undergo a dramatic reordering, we as Christians seem to be pining for prophetic voices and the theoretical footing from which to gain a purchase on the slippery slopes of contemporary religious life. Could it be that the subtle forces at work in the interior lives of Fr Bede Griffiths and Dom Henri Le Saux, compelling them to take the radical steps they did more than a half a century ago, are the very forces operative in the lives of thousands, or perhaps even millions of Catholics around the world today? Could it be that it is theirs and other similarly prophetic interventions that offer one of the keys to the current crisis in religion today? Could it be, ironically, if not providentially, that the unfamiliar epistemologies and theologies of other faiths, while, in one way of looking, present challenges to the Christian ethos, might also be the very remedy by which we as Christians (in the West, at least) could reinvigorate, inspire and recover our own spiritual vitality and deepen the Christian experience? If so, could we undertake such an endeavor without betraying the spirit of our own heritage? Speaking as a monk, Merton offers this response:

“I think we have now reached a stage of (long-overdue) religious maturity at which it may be possible for someone to remain perfectly faithful to a Christian and Western monastic commitment, and yet to learn in depth from, say, a Buddhist or Hindu discipline and experience. I believe that some of us need to do this in order to improve the quality of our own monastic life and even to help in the task of monastic renewal which has been undertaken within the Western Church” (Asian Journals, p. 313).

It is fascinating to hear how similar the stories told by pilgrims of various Christian denominations from diverse parts of the world are. What we hear each year from seekers coming to Tamil Nadu is an intense longing to explore the deeper questions of life and faith, and to heed the call of the ‘inner’ monk or nun that invariably dwells within each us. As lay monasticism continues to grow—expressed in increasing oblate membership rolls in various communities around the world, not least of all, at Shantivanam—what we see in seekers today is a sense of urgency, a healthy desperation and quiet yearning to find solid and committed faith communities engaged in the genuine search for spiritual wholeness. Where, they implore, is truth beyond the sham consumer humdrum that floods and saturates the planet’s life-world on a daily basis? Where and how in an increasingly desacralized info-saturated consumer world is one to encounter silence and the Sacred?

A stream of refugees appears each year in South India, perhaps with slightly romanticized expectations as to what is to be found here and yet, with an unquestioned sincerity. What a blessing and joyful surprise it is for them to discover that not only are they not alone in their quest but that others—Fr. Bede and Sw. Abhishiktananda not least of all among them—have marked the way. Nearly twenty years after Father Bede’s passing and almost forty years after that of Swami Abhishiktananda, the social, theological, and liturgical experiments these two monks initiated more than a half a century ago offer encouragement and orientation in an increasingly complex, centrifugal postmodern world. It is perhaps only now that the insights and ideas of these towering figures are coming into their own, finding a sympathetic listening and the broader audience they so deserve, and thus are finally attaining fulfillment in the promise of serving this and future generations of seekers and believers.