MAN, MONK, MYSTIC

by Pascaline Coff, OSB

Bede Griffiths was a monk, a man in whom there was no guile, and was last to see the guile that may have been in any other. This monk with a universal heart was an icon of integrity and guilelessness. As John Henry Cardinal Newman once described them, Bede was one of those:

Bede Griffiths was a monk, a man in whom there was no guile, and was last to see the guile that may have been in any other. This monk with a universal heart was an icon of integrity and guilelessness. As John Henry Cardinal Newman once described them, Bede was one of those:

who live in a way least thought of by others, the way chosen by our Savior, to make headway against all the power and wisdom of the world. It is a difficult and rare virtue, to mean what we say, to love without deceit, to think no evil, to bear no grudge, to be free from selfishness, to be innocent and straightforward… simple-hearted. They take everything in good part which happens to them, and make the best of everyone. (homily, Feast of St. Bartholomew)

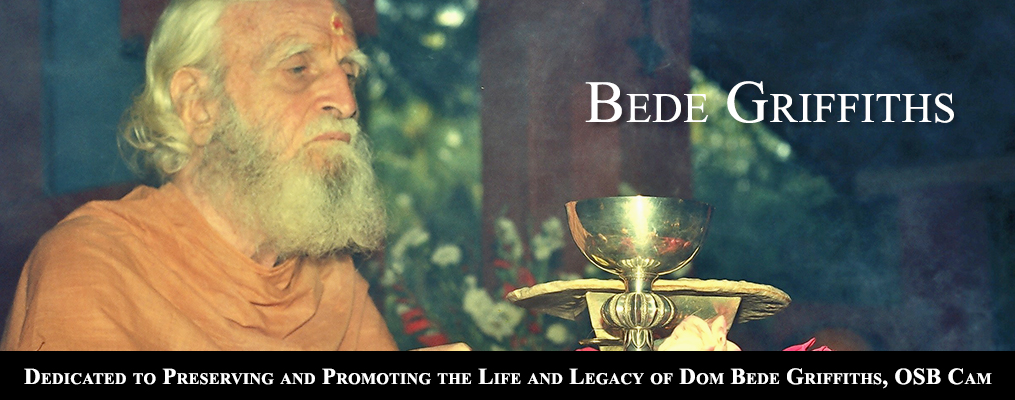

Such was Father Bede Griffiths, Swami Dayananda, who died May 13, 1993, barefooted and clothed in the color of the sun, in his thatched hut at Shantivanam in South India.

Life, 1906-1993

Alan Richard Griffiths was born at home at Walton-on-Thames in 1906 in a British middle class family, youngest of three. He had a sister and a brother. Soon after his birth Alan’s Dad lost his business, cheated by a partner to the last penny. Mr. Griffiths lost face and never regained his role or place in the family. Alan’s mother, who then became both parents to the children, had to move to less comfortable surroundings and had to go to work and manage her own housecleaning.

Education, 1918-1929

At the age of 12 Alan was enrolled in a public school for poor boys, known as Christ’s Hospital. The students were nicknamed the “blue coats.” This tall, lean, poor boy, ranked first in his exams, as you may have guessed if you knew Bede Griffiths at all in later life. Receiving a scholarship to Oxford, Alan want on to study English literature and philosophy from 1925-1929. Poetry, a lifelong love for Alan, was a step toward living out the full interiority of his spirit. It was during his third year at Oxford that C.S. Lewis became his tutor and the two became great friends, searching together for the Ultimate and some form of fitting religion. Alan graduated in journalism which prepared him well for the 12 books he would later author and the multitudinous articles and conferences.

Experiment in Common Life, 1930

Soon after graduation, Alan began what he and his two companions called an “experiment in Common Life.” With Hugh Waterman and Martin Skinner, he purchased a country cottage in Cotswalds, and took on a lifestyle immersed in nature, as a protest against contemporary life. Mrs. Griffiths made them three wool vests. For their part, the three young men milked cows and sold the milk. They read the Christian Bible together as literature, much impressed with the connections with nature as they lived out their experiment. One of the three found the life too austere and before the year ran out left the group and the experiment concluded. It had been brief but had a profound effect on Alan.

Conversion, 1931

Alan Griffiths then applied for ministry in the Church of England. However, he was advised to first go work in the slums of London. The confusion that ensued with him between his rational mind end his spirit almost broke him. He sought out a retreat during which he fasted, prayed all night until tears flooded him and he had a tremendous breakthrough. As he himself wrote, “I was no longer the center of my own life.” But the breakthrough was not complete. Alan went back to Cotswald, lived on turnips, grew weaker and confused again. Therefore he was moved to spend the day in prayer surrendering this time in a closet, visualizing himself at the foot of the Cross. Alan was swept into “real prayer” and later described this as his own “return to the Center.” He went to work and ate at the farm next door, joined the family and began to read Cardinal Newman’s Development of Christian Doctrine.

Roman Catholicism and Monastic Life, 1931-1937

Deeply touched by the reading both intellectually and spiritually, in spite of the fact that his mother had verbalized that her greatest grief would be if any in her family would embrace Roman Catholicism, Alan visited Prinknash Abbey and remained six weeks, much impressed. On Christmas eve, 1931, he was received into the Church and at midnight Mass received his first Communion. Alan then entered Prinknash Abbey just a few weeks later. Here, he said, he felt at home. Later with tongue in cheek he said, “Downside would have ruined me as it was too intellectual.” On December 20, 1932, Alan was clothed as a Benedictine Novice and received the name of Bede, which means prayer. Years later in India, he received the name of Dhayananda which means bliss of prayer, and still later Dayananda, which means bliss of compassion. Fr. Bede offered his Perpetual Vows in 1937, just one year before his beloved mother met with a car accident and passed away. He was ordained in 1940 at the age of 34. One of the monastic tasks he most enjoyed was guest master, since the Abbey attracted people from different cultures and walks of life. The exchange was energizing.

Prior, 1947-1951

Once when Fr. Bede’s Abbot was ill and unable to deliver a lecture in Glasgow, the young monk was sent to fill in. He made such an impression on all that the Abbot then chose Fr. Bede to be Prior of a group of 25 monks being sent to “bail out” two French monasteries. His was that of Farnborough. But endowments were dreadfully insufficient, and in four years’ time, Bede Griffiths was unable to generate more, so the Abbot then sent him on to the other French monastery, Pluscardin, in Scotland. Fr. Bede described this place as being very cold. It was then that he was encouraged to write his story which eventually was published as his autobiography, The Golden String (1954).

India, 1955-1993

During his years at Farnborough, Bede had met Fr. Benedict Alapott, an Indian priest born in Europe, greatly desirous of starting a foundation in India. Fr. Bede had been introduced to Eastern thought, Yoga and Indian Scripture by a Jungian analyst, Tony Sussman.

When Fr. Griffiths asked permission to go to India he was refused because the Abbot said “there is too much of Bede Griffiths’ will in this.” Later, however, the Abbot saw fit to “send” Fr. Bede, but the venture was not to be a foundation from Prinknash. Fr. Bede was to be henceforth subject to a Bishop in India, which meant that eventually his vowed status with Prinknash Abbey would expire. Of all this he wrote: “The surrender of the ego is the only way of life.” And again, “The surrender of the ego is the most difficult thing we have to do.” In leaving for India, his spirit was lighthearted as he wrote to a friend, “I am going to discover the other half of my soul.” In 1955, Fr. Bede and Fr. Benedict took a ship to Bombay, and after pilgrimages to Elaphantes and Mysore, they settled in Kengeri, Bangalore, the garden spot of India. But this was only to last until 1958 when Fr. Bede joined Fr. Francis Acharya in Kurisumala for ten years. Fr. Bede said of life at Kengeri, “It was too Western.”

Kurisumala, 1955-1968

The Mountain of the Cross (Kurisumala Ashram) was located on 100 acres of donated land in the ghats of Kerala. Fathers Francis and Bede used the Syriac rite and developed a fitting monastic liturgy in that language. Wanting to enter into the tradition of Indian Sannyasa (monk hood) and to establish a Christian ashram, they dressed in Kavi orange robes, and Fr.Bede took the Sanskrit name, Dhayananda. During his time there, Fr. Bede wrote Christ in India and studied the religions and culture of India which he had loved from the start. In 1963, Bede Griffiths was invited to New Mexico to give lectures at an East-West Dialogue Meeting. During this same trip to America, he was interviewed by CBS, and gave lectures to 500 Missionary Sisters at Maryknoll, N.Y.

Shantivanam, 1968-1993

Shantivanam, the ashram in Tamil Nadu dedicated to the most Holy Trinity, (hence the name in Sanskrit: Saccidananda), had been founded in 1950 by two French priests: Fr. Jules Monchanin, a diocesan missionary, and Fr. Henry leSaux (Abhishiktananda) from the Abbey of Kergonan. Fr. Monchanin arrived in India in 1939 and first lived with the Bishop, then in a rectory in Kulithalai. Only in 1948 did a donor offer a few acres in Trichy near the Kavery River where he and Abhishiktananda began worshipping in a tiny chapel that they had built with their own hands in Indian style. They used English, Sanskrit and Tamil in their liturgies, meeting three times daily for common prayer, using scriptures of the different religions, using the Roman rite themselves. They lived in thatched huts, the real poverty of the poor in India. On October 10, 1957, Fr.Monchanin died in France where he had gone for surgery. Abhishik stayed on at Shantivanam but travelled up to the caves in the Himalayas off and on until he asked in 1968 that someone from Kurismula come and he retired to the North. His heart gave out in Rishikesh and he died December 7, 1973.

In 1968, Father Bede Griffiths arrived at Shantivanam from Kurisumala with two other monks and again immersed himself in the study of Indian thought, attempting to relate it to Christian theology. He went on pilgrimage and studied Hinduism with Raimundo Panikkar. Under Fr. Bede’s guidance Shantivanam became a center of contemplative life, of inculturation, and of inter religious dialogue. He contributed greatly to the development of Indian Christian Theology. In 1973 he published Vedanta and the Christian Faith. The first copies of Return to the Center arrived in time to be the centerpiece in the temple kolam for Father’s 70th Birthday, December l7, 1976.

In 1979, our monastic East-West Dialogue Board, NABEWD, invited Fr. Bede to come be a “roving lecturer” in our American Monasteries. The fruit of this became his volume entitled, The Cosmic Revelation, most of which lectures he gave at Conception Abbey in Missouri. Again in 1981, the Board invited Fr. Griffiths to come be keynote speaker at our Conference, “Formation and Transformation from an Eastern Perspective,” in Kansas City, Kansas. The fruit of this became the set of audio tapes from Credence called, “Riches from the East.” Back at his ashram in South India, Fr. Bede gave daily teachings on the Vedas, homilies at Eucharist and Vespers, throwing shafts of penetrating light into the Christian mystery. His complete commentary on the Bhagaavad Gita appeared in 1987 under the title, “Rivers of Compassion.” By 1989, Fr. Bede had completed another volume called The New Vision of Reality, which together with The Marriage of East and West, (1952), is his most popular. The latter has been translated into some six languages. In between the books he authored, there were countless conferences and articles he penned by hand together with voluminous mail.

Illness and Mahasamadhi

On January 25, 1990 Bede Griffiths suffered a first stroke in his hut at Shantivanam. One month to the day in February, he was cured in a struggle with death and divine love. He later described this as an intense mystical experience. By May of that same year he was in the USA. Among many other lectures and conferences he gave the John Main Lectures at New Harmony, Indiana, now published as The New Creation in Christ. Soon afterward, Fr. Bede completed his final work, not yet published, Universal Wisdom. He visited the USA again in 1991 and 1992, giving roving lectures before going to England, Germany and Australia. While in Australia he met with His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, and the exchange was enriching for both. Afterwards Fr. Bade said, “I do believe he liked me!” He took the long way home, giving more lectures in Germany and England. His heart was fluttering but he was always energized by all that went through him. He arrived back at his ashram in S. India in October. An Australian film team was awaiting him. “A Human Search” was successfully completed just three days before his final stroke on December 20th – three days after his 86th Birthday. On January 24, Bede Griffiths had a series of strokes which finally brought him to his Mahasamadhi on May 13, in his hut at Shantivanam in South India, surrounded with much tender loving care. Father Bede Griffiths was laid to rest nearby the temple, next to one of his first disciples, Fr. Amaldas, who, half Father’s age, died some years before him.

The Man

Bede Griffiths was a man with a universal heart. He had no guile and saw no guile in others. He honored the sacredness of every person because he believed so deeply that each person is a unique image of the divine. With Ruusbroec, Fr. Bede believed that “God’s work in the emptiness of the soul is eternal.” He all but saw that “spark of God” in everyone. He loved to describe the divine processions within: the Father in Self-reflection bringing forth His Word, His divine Image in pure consciousness in perfect bliss: self-knowing and self-giving. And the whole creation comes to its fullness in this intimacy, this relationship of love. Fr. Bede was fascinated by the Trinitarian Mystery, and even more so by the possibilities the Hindu doctrine of Saccidananda presented our Christian theology. (Cf. Toward a Christian Vedanta, by Wayne Teasdale).

Bede Griffiths had a listening heart that was finely attuned to others and therefore many others came to open their hearts to him. Someone has said so truly, of all the things he was, Bede Griffiths was the perfect gentleman to the End. And it was this listening heart that awaited everyone who came. He even sought out new arrivals to set up a time to share with them. If the deepest meaning of hospitality is “receiving the Divine,” Bede Griffiths surely did just that in each one who came into his ambit. Those who left his presence frequently remarked that he treated them as if they were his only business that day; he made them feel so revered.

For Fr. Bede, being universal meant to be centered and grounded. He generated this universality of heart through his daily practice of meditation and contemplative prayer, and this opened him ever more to the myths, symbols and teachings of the other great religions of the world. He was intrigued by the concept of the archetypal or Universal Man. In several of his books one can find how he detailed the names and descriptions of such from all the major religions. (cf The Marriage of the East and West, p.140; 70). He loved to quote the Chandogya Upanishad (8,3) to show that while our body takes up only a small space on this planet, our mind encompasses the whole universe:

There is this city of Brahman (the human body) and in it there is a small shrine in the form of a lotus, and within can be found a small space. This little space within the heart is as great as this vast universe. The heavens and the earth are there, and the sun and the moon and the stars; fire and lightening and wind are there, and all that now is and is not yet – all that is contained within it.

Bede Griffiths had loved and assimilated his earlier studies and reading so well that his universal heart could quote a Upanishad committed to memory as easily as a line or stanza from William Blake, Gerard Manley Hopkins or others. “Touch the wing of a butterfly and you move a star.” He delighted in describing the interconnection, interrelationship of everything (cf New Vision of Reality).

Already in 1940, at the time of Ordination, Bede Griffiths’ heart reached out to the universal Lord. As an octagenarian, with a twinkle in his eye and in his throat, he told me while walking on a country road in the mountains in Vermont, that on his Mass Card he put the words, “Priest forever according to the Order of Melchesidech,” the universal priesthood. Then too, his final book, published posthumously, is entitled, Universal Wisdom. He was indeed a man with a universal heart and a universal God.

After his first stroke his intuitive mind was vibrant with insights on the divine mysteries, while his heart often suffered from some new insight of discrepancy in the Bible, or with injustice. He was convinced that the Old Testament has to be re-read in the light of the life and teachings of Christ. Jesus’ prayer to his Father “that they may be one as we are one,” (Jn. 17:2l) consumed Father Bede’s great heart.

The Monk

For Alan Richard Griffiths to be a Christian was simultaneously to be a monk! In much less than one month after his reception into the Roman Catholic Church he became a postulant at Prinknash Abbey. His clothing with the monastic habit the following year was for him a “sign that you were putting on Christ,” and the new name, Bede, signified that he “had become a new man in Christ.” But already as a Postulant, life in the monastery was much less austere than the life Alan had lived since College. Therefore, his first monastic crisis arose. He asked to visit a Cistercian monastery and discovered that his imagination had played tricks on him. As austere as it was, the Cistercian life would not have fit him at all, so he returned to Prinknash humbled and happy. In reading the New Testament and Abbot Marmion’s Christ the Ideal of the Monk, Christ’s life of humble obedience to his Father’s will astounded this Postulant, especially that he had not noticed this before. He was beginning to see how he had controlled his life by his reason alone, and it was dawning upon him that “the greatest obstacle in life is the power of self-will.” (cf Golden String, p.135). He recalled from reading Marcis Arelius that there is a divine order in the universe…and to discern the divine will beneath all the events of daily life and to adhere to it with one’s own will was the source of all happiness. (Golden String, p.136)

This profound insight was to be tested by fire when the young Father Bede asked his Abbot permission to go to India. He was told “no” because there was too much of Bede Griffiths’ will in this. The Abbot was wise enough to recognize how much of the Divine Will was in it also, and later “sent” Fr. Bede to India. “The surrender of the ego is the most difficult thing we have to do,” Bede wrote, and insisted “The surrender of the ego is the ONLY way of life.”

In the light of this it is easy to see how Indian monkhood so easily attracted Fr. Bede. The monk in the Hindu tradition is called the Sannyasi – the renunciate. And of all that is renounced, the most essential is the self. Little wonder Fr. Bede was ever concerned for the “return to the center,” our true center. “The problem with human existence is that we all have a self-centered personality,” he once said in a talk on religious vows. And it was monastic vows that he saw as the help to free us from our selfishness. In the Indian Independence leader, Gandhi, Bede saw the same insight:

What Gandhi saw so clearly is that this detachment was not a way of escape from the world but of a freedom from self-interest which enabled one to give oneself totally to God and to the world. (Christ in India, p.24)

Father Bede lived as he wrote – a monastery must always be concerned with the “search for God,” the continual effort to “realize” God, to discover the reality of the hidden presence of God in the cave of one’s heart or depths of the soul. (Christ in India, p.24). For Bede Griffiths, the monk was one who has found the true center, and therefore the real call of the monk is to renew and share this awareness of the center.

He was ever faithful to his monastic office and community prayer and always stopped at the first sound of the bell. He radiated when sharing on the Scriptures even when he found contradictions in many places. He was a contemplative through and through. Contemplation was the basic dynamism of his life, and he believed it was meant to be the aim of all human life. His letters, conferences, homilies and personal exchanges were all so enriching because all proceeded from this contemplative dimension deep within him. Bede Griffiths has been called the “equivalent to the Hesychast,” one who goes beyond silence to stillness of heart. He saw the contemplative process not only as one of transcendence but also a painful experience of self-discovery, “initiating an experience of self-knowledge and purification, shattering the illusions we have about our self, the nearer we draw to this Transcendent Mystery.” (Judy Walter’sInfluence on My Life, 5/31).

In the talks he gave at New Harmony, the year before he died, Fr. Bede strongly urged the laity to form small groups of contemplative prayer. He also laid the groundwork for a society for the renewal of contemplative life in the world.

Father Bede’s keen interest and involvement in East-West Inter-monastic dialogue flowed naturally from this contemplative dimension. His contribution to the dialogue throughout the world is immeasurable, much of which is yet to be uncovered. But for those who were blessed to be present during any of the exchanges, his presence was immediately giftful, his words insightful, and his manner attentive and respectful. Needless to say, his celebration of Eucharist was profound, not only for himself but for all who participated.

The Mystic

Bede Griffiths was granted mystical experiences both before and after attending Oxford. As a high school lad, when walking through the playing fields he was totally transformed at sunset while birds were singing like never before. The Hawthorne trees were in bloom, but again, like never before. He felt an awe and knelt on the ground. Nature began to wear a kind of sacramental character from then on, and every sunset thereafter brought a sense of religious awe, in the presence of an unfathomable Mystery. After graduation from Oxford, his mystical experience was as the other side of a two-edged sword, “the initiating experience of self-knowledge and purification, shattering the illusions…” His work in the slums of London brought him to his knees in utter confusion. He fasted and prayed all night until tears brought a tremendous breakthrough and he realized he was no longer the “center of his own life.” He was relieved but still confused. This time he spent the entire day in prayer but thought it had only been two hours. Fr. Bede surrendered to the Crucified One and had an astounding breakthrough, being swept up into what he called “real prayer.” This he referred to as his own “return to the Center.” It was soon after this that he entered the Roman Catholic Church and then the monastery. These were mystical experiences, moments, hours which brought awe and transformation: a sense of oneness with intensely sharpened senses, deep spiritual delight and a yet unknown sense of belonging in the universe, belonging where he was.

But a mystic is one who reaches a more or less continuous state of transformation, with a constant sense of union, of divine communion. This was to come to Fr. Bede in his later years through the instrumentality of his first stroke. He looked back upon his stroke as having three levels of influence on him: body, soul and spirit. Spiritually, he described it as his “advaitic experience.” In the Hindu tradition, that is often referred to as a unity that is no longer two: “Not two, not two” they say. Fr. Bede spoke of it as being the awakening of his repressed feminine side which demanded attention and integration. A cure 30 days after the stroke he called an intense experience of the divine feminine, loved like never before. He wept and could not speak for days. A disciple close to his heart took notes of his words:

This was not merely a psychological analysis, but a deeply contemplative look at the overwhelming inner experience he had gone through. Intimating it was a mystical experience which could not properly be put into words, Father used symbolic language to try and express the depth of the experience. The two symbols he used were the Black Madonna and the Crucified Christ. He said these two images summed up for him something of this mysterious experience of the Divine feminine and the mystery of suffering.

When he first spoke about the Black Madonna, he said his experience of her was deeply connected to the Earth-Mother, to the forms of the ancient feminine found in rocks and caves and in the different forms in nature. He likened it to the experience of the feminine expressed in the Hindu concept of Shakti – the power of the Divine Feminine. Later Father wrote these reflections on the Black Madonna: “The Black Madonna symbolizes for me the Black Power in Nature and Life, the hidden power in the womb…I feel it was this Power which struck me. She is cruel and destructive, but also deeply loving and nourishing.”

A few months later Father again wrote:

The figure of the Black Madonna stood for the feminine in all its forms. I felt the need to surrender to the Mother, and this gave me the experience of being overwhelmed by love. I realized that surrendering to death, and dying to oneself is surrendering to Total Love.

Regarding the image of the Crucified Christ, Father made the statement that his understanding of the crucifixion had deepened profoundly. He wrote:

On the Cross Jesus surrendered himself to this Dark Power. He lost everything: friends, disciples, his own people, their law and religion. And at last he had to surrender his God: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.” Even his heavenly Father, every image of a personal God, had to go. He had to enter the Dark Night, to be exposed to the abyss. Only then could he become everything and nothing, opened beyond everything that can be named or spoken; only then could he be one with the darkness, the Void, the Dark Mother who is Love itself…

Then a final quote from a talk that he gave in Jaiharikal in May, 1991:

I would like to share with you something of my advaitic experience…I was overwhelmed and deluged with love. The feminine in me opened up and a whole new vision opened. I saw love as the basic principle of the whole universe. I saw God in the earth, in trees, in mountains. It led me to the conviction that there is no absolute good or evil in this world. We have to let go of all concepts which divide the world into good and evil, right and wrong, and begin to see the complimentarity of opposites which Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa called the coincidentia oppositorum, the “coincidence of opposites.”

I believe that from the time of his first stroke in l990 until his death, Father was contemplatively undergoing this struggle of the coincidence of opposites. The mystical language he uses in the image of the Black Madonna and the Crucified Christ speak of the profound depth of this integration, and also the fact that this coincidence comes in the form of the Cross.

His attitude was one of surrender and observation, allowing the process to unfold without analysis or interference. I believe this was a deeply contemplative response to the process of final integration that was taking shape in the depths of his being. Father’s openness and receptivity of this integration could only come from a lifetime experience of contemplative living. (Judy Walter, “Father Bede’s Influence on My Life,” Shantivanam 5/l3/94)

After the stroke and the cure, father Bede did a great amount of travel to foreign countries. He said he never lost this sense of the divine presence from that time on. In a brief explanation he offered his overview of life in contrast to what society teaches us, he said at the age of 85 he begged to differ with those who think that life is all over at 40, and that from then on we go downhill. He saw our lifetime as roughly divided into three interrelated phases: ages 1-20, during which time our bodies develop, our mind and character gradually grow to maturity; then ages 20-40, during which time our psychological faculties are developed, many people marry at this stage and rear a family, professional skills are acquired, sports and arts are perfected. But most people think or are taught that that’s all there is and it’s all down hill from there. Father Bede insisted that the time from age 40 on is what life is all about; all the rest was preparation for the flowering of the whole personality. For him, here the spiritual powers begin to develop and transcend the capacities of mind and body. These are not left behind but are integrated into what opens us to the Eternal, the discovery of the Absolute, the Transcendent, the deep Source of all Reality. This is the breakthrough to the mystical and this, Fr. Bede believed, is the great hope for everyone. He said the last 20 years of his life were the most wonderful of all. This man, monk, and mystic, left us a message not only in his words but most of all by his very life!

_________________________

Sr. Pascaline Coff is the foundress of Osage Monastery, a monastic ashram in Sand Springs, Oklahoma USA and has been involved with East-West Interreligious Dialogue for more than 20 years. She spent one year in prayer and study with Fr. Bede at Shantivnam Ashram in S. India and was past Co-Chair of the Bede Griffiths International Literary Trust.